How to Dollarize Argentina

The topic of dollarization in Argentina has left many confused about its feasibility and implementation. In this post, I aim to provide a pedagogical discussion of the proposal I started to work with Emilio Ocampo in the Fall of 2020.

Before delving further, it’s essential to emphasize that the Argentine economic situation changes on a daily basis, meaning that the approach to implementing a proposal like this one may change over time. However, the key is to grasp the structure and concept behind this proposal’s work. Secondly, this proposal assumes implementation under a new democratically elected government committed to credible structural reforms. There is a regime change between now and then. Evaluating our dollarization proposal in the current context would conflate how to dollarize (our proposal) with when to dollarize (a political issue).

What Needs to Be Dollarized?

I find it useful to simplify the process by categorizing what needs to be dollarized into three groups of peso-denominated liabilities or “buckets.” Each group can be dollarized differently, requiring varying central bank reserves and timeframes.

Bank Deposits

Dollarizing bank deposits is the most straightforward aspect of dollarization. This process involves converting peso deposits into dollars at the dollarization rate, essentially an accounting adjustment. All peso-denominated bank accounts would be redenominated in dollars.

Some argue that this would likely trigger a bank run as Argentines seek to secure their wealth in dollars. I will address this concern in my next post, explaining why I think the likelihood of such an event is low.

It’s important to note that a successful dollarization of bank deposits does not require many dollars at the central bank.

Currency in Circulation

Converting currency in circulation into dollars can be done in three ways. One option is a compulsory exchange similar to Ecuador’s approach, where the government initially set a nine-month period to exchange sucres for dollars at a fixed rate.

Another way is voluntary dollarization, as seen in El Salvador, where the colones bills do not lose their validity or “expire.” Note that in this case, the central bank does not need to exchange its currency in circulation for dollars; it can let the public voluntarily dollarize by either making a bank deposit or paying taxes.

The third option is a voluntary + automatic referendum dollarization. This method is a combination of Ecuador and El Salvador methods. In this case, Argentina could start with a voluntary dollarization and transition to a compulsory one if the volume of pesos in circulation falls below a given threshold at a given date. This approach allows the government to obtain the necessary dollars to dollarize the remaining currency in circulation.

The following plot shows the evolution of currency conversion in Ecuador and El Salvador on a monthly basis. Each bar tracks the percent of the initial stock that remains in circulation. Unsurprisingly, Ecuador’s currency dollarized faster than that of El Salvador. Even more, Ecuador central bank net reserves did not decline as sucres went out of circulation (because they were dollarized in the form of bank deposits). An important lesson from this graph is that there is no need to have 100% of dollars to convert currency into circulation on day one.

Especially in a voluntary or voluntary + automatic referendum scheme, the central bank does not need many dollars to initiate the dollarization process.

A final clarification. The fact that in terms of currency in circulation, the peso and the dollar coexist for some time does not mean this is a currency competition theme. Recall that all bank deposits are dollarized, and the exchange between the peso and the dollar is fixed. Since the currency in the hands of the public cannot be dollarized overnight, there is always a period where both currencies co-exist.

Central Bank Liabilities

The problem

The Argentine central bank’s inability to use Argentine treasury bonds for open market operations has led to the issuance of its short-term liabilities, known as letras de liquidez (Leliqs or liquidity bills). These bills, held by banks as counterparts to deposits, currently amount to nearly 400% of base money. Given the lack of net reserves or usable financial assets, the central bank can only roll over these liabilities or risk hyperinflation. Given the present context of the Argentine economy, it is heroic to think that a positive shock to money demand can increase the amount needed to quietly absorb the Leliqs.

The central bank liabilities problem needs a solution other than a “haircut” or yet another Argentine violation of contracts. The intention behind developing an instrument like the one discussed in this section is to allow for clean dollarization of central bank liabilities.

The central bank’s debt is ultimately the National Government’s debt. The National State should not ignore this debt. Not paying it or repudiating it would have grave consequences for Argentina's financial system and the status of the new government. As Argentina does not have a developed capital market, banks are the main source of meager financing for the private sector.

The proposed solution: The MSF

The proposed solution to this central bank liability problem uses a special-purpose vehicle called the Monetary Stabilization Fund (MSF). The MSF is located in a safe international jurisdiction.

The MSF has two groups of assets. The first group is a portfolio of dollar bonds issued under NY law that replaces the non-transferable bonds (LI) and the transitory advances to the government (AT) currently held by the central bank. The second group is other financial assets contributed by the government and diversify the cash flow of the MSF. These are two examples of what the other financial assets could be:

Dividends and coupons: the seized private retirement and pension funds.

Cash: a share of export tariffs.

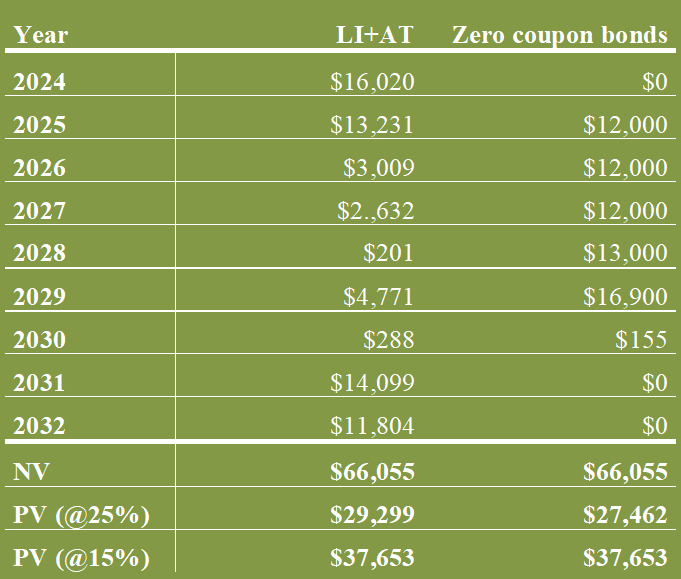

There are endless ways to replicate the nominal and present value of the LI+AT portfolio. The following table is just one example assuming the new dollar bonds are zero-coupon.

It is crucial to note that the bonds swapped by the treasury are NOT sold in the market; they are directly transferred to the MSF. Argentina is not testing the market’s bond appetite (we already know there will likely be none for a while). Because the new bonds have the same nominal and present values, there is no change in the debt amount of Argentina. The change is that intra-government debt is now foreign (sovereign) debt.

The MSF’s liabilities are non-recourse asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) that replaces central bank liabilities. A credit enhancement, such as acquiring a guarantee (say, for 30% of ABCPs) and a backstop underwriting facility, would further increase the risk profile of the MFS.

As these assets produce a cash flow, MSF automatically pays off ABCP. If the MSF receives $20 and ABCP debt amounts to $100, then it cancels ABCP by this amount and rolls over the remaining $80. MSF repeats the process until all ABCP is paid off. Once all ABCP is paid off, the MFS would be automatically liquidated, and the government securities would be automatically canceled.

Additionally, the MFS may be allowed to sell part of the nationalized retirement portfolio if its market value exceeds its high historical value. In this case, the sale proceeds must be used to cancel ABCP.

Successful implementation of the MSF can lead to the most important reduction in the country’s external debt without involving a default in Argentine history.

The MFS would have a better credit profile than the Argentine government for all these reasons. In a sense, the MFS would succeed in doing what the Brady Plan did with US banks, “freeing” them from an unattractive asset so that they could lend money to the private sector. In both cases, the mechanism is securitization with credit enhancement. This proposal’s central idea is to transform a low-quality asset with no liquidity into a more attractive, liquid asset for the financial market.

The following figure shows the composition of the balance sheet of the ABCP. The figure also shows the potential gain in collateral if there is a fall in the discount rate. It also shows that MSF can repay the ABCP may be able contribute with dollars if needed to swap currency in circulation of deposit withdrawals.

How long does dollarization take?

This is a tricky question. As we just saw, to dollarize different peso-liabilities entails different timeframes. The MSF may take a few years to dollarize and pay off all central bank liabilities. However, for the public, dollarization is quite fast. Bank deposits can be dollarized immediately by converting the deposits at the exchange rate. Circulation can be withdrawn between one or two years, but because the conversion rate from pesos to dollars is fixed, this up-to-two-year period is of little concern (especially because individuals can get rid of pesos by paying taxes). For the public, dollarization takes place quite fast.

A few final considerations

First. ABCP is a tradable security in the international market. Therefore, Argentina banks that originally held central bank liabilities are under no obligation to keep ABCP until MSF completes paying them all off.

Second. An investor may be interested in purchasing ABCP at a high discount rate (a likely scenario on the onset of dollarization), holding them, and benefiting from a future fall in the discount rate. This arrangement (if possible) would reduce the risk of a fire sale of ABCP on the secondary market by Argentine commercial banks.

Third. The MSF has a convenient flexibility. By swapping the LI+AT held by the central bank, the Treasury can give itself a grace period by postponing when the first bond payment takes place (see the above table with a year grace period). Additionally, given its fiscal needs, the treasury can adjust how long it would take to pay off all ABCP. If, for instance, paying off all ABCP in four years imposes too much fiscal pressure, the Treasury can consider a longer term. This is a convenient feature since the Treasury can no longer roll over the LI.

This post is an adaptation of the following Spanish text.

Next: Dollarization and bank runs.