Javier Lanari, Milei’s Media Sub-Secretary, claimed that Argentina’s annual inflation dropped from 17,000% to 8% in record time. This statement has been heavily promoted by Milei’s administration, likely for political reasons—face-value numbers are easy to market as a success. However, I question the use of these figures, as well as Lanari’s enthusiastic yet premature assertion that this represents a record in disinflation speed.

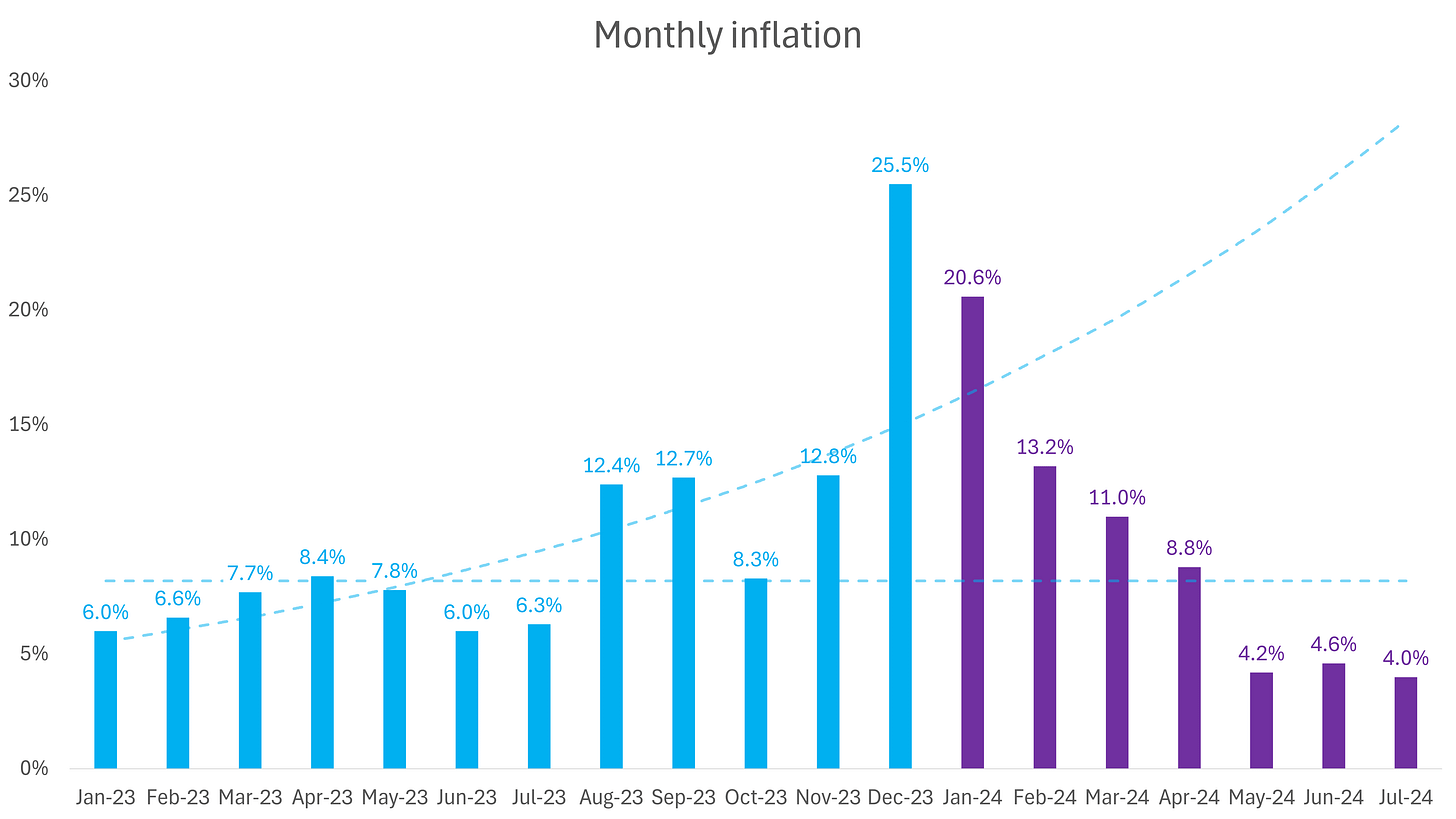

Let’s begin by examining the official data. Figure 1 shows the monthly inflation rate since January 2023. The light blue bars represent monthly inflation during the Kirchnerista administration (under President Alberto Fernández), while the purple bars correspond to Milei’s presidency.

You might wonder where the 17,000% inflation rate comes from. No one seems to know for certain. But the 17,000% is an annualized rate. Annualizing and comparing a monthly rate with a non-annualized one is an unimpressive trick. The 17,000% annual inflation rate translates to a 53.5% monthly rate. However, the highest monthly rate in the chart is less than half of that figure. Even if you consider core CPI (not shown in the graph), the peak inflation rate during the Kirchnerista period was 28.3% in December 2023.

Not only the origin of the 17,000% figure is unclear, but using it appears to be a sloppy attempt to exaggerate the disinflation process during Milei’s first months in office. This kind of statistical manipulation is reminiscent of Kirchnerista practices and is unnecessary.

But there’s more to consider in the data. A clear spike in inflation occurred in December 2023 and January 2024. I view this spike as transitory, not permanent. Three shocks explain this surge:

Massa’s plan platita

Devaluation in August 2023 (roughly from 275 to 350 pesos per US dollar)

Devaluation in December 2023 (roughly from 400 to 800 pesos per US dollar)

While these shocks can have a permanent effect on the price level, their impact on the inflation rate is temporary. Therefore, these elevated inflation rates are not typical and, as such, a biased benchmark. The average monthly inflation rate before the spike is 8.2% (as indicated by the horizontal dotted line in the plot). Short of a hyperinflation scenario, the inflation rate was expected to return to pre-election level and trend. Even if we include all 2023 inflation rates and fit an exponential trend, the peak inflation rate is below 30%, occurring in July 2024. By this point, attributing this to the Kirchnerista administration is a stretch.

And because these shocks have a transitory effect on inflation, the counterfactual hyperinflation scenario does not have a 100% chance of happening. Another reason to doubt the exponential growth is that Rubinstein, the Vice Minister of Economics during Fernandez’s presidency, stated that they agreed on the need to get back to fiscal balance. Granted, statements coming from Kirchneristas are not particularly credible.

Milei’s supporters have put forth various arguments to justify the 17,000% figure, but I find them to be non-sequiturs. Simply disputing the 8.2% inflation rate (admittedly a simple calculation to use as a reference) does not prove that the 17,000% figure is accurate.

One argument, for instance, points to the existence of price controls before Milei took office. However, these controls did not prevent the inflation rate from tripling between October and December. Moreover, the general and regulated monthly inflation rates for 2023 were 9.5% and 8.1%, respectively—not a significant enough gap to justify the 17,000% figure. Since December 2016, the difference between the CPI and regulated CPI has been 44% (equivalent to 7,881% annually). For regulated prices to contribute sufficiently to the CPI, the pending inflation rate would need to be significantly higher than 17,000%. At this point, coming up with the 17,000% seems too much like cherry-picking.

The price control argument also has some blind spots. Milei has implemented price controls as well. A notable example is health insurance. Following price deregulation, health insurance costs rose 150% within the first three months of 2024. These prices had been frozen since 2019, during which time accumulated inflation reached 1,243%. After deregulating their prices, Economic Minister Caputo claimed that health insurance companies were declaring war on the middle class. In response, Milei’s “libertarian” government accused these companies of cartelization (even though the price increase was still below accumulated inflation) and re-regulated their prices. Milei’s price control now states that health insurance prices cannot increase more than the inflation rate.

Another argument suggests that I’m overlooking the lag between a monetary shock and its impact on the price level. This refers to the concept of long and variable lags in U.S. monetary policy. However, Argentina’s economy is very different from that of the U.S., and anyone familiar with Argentina’s monetary policy would observe that the lag is significantly shorter. And, once again, the reasons behind the spike in inflation were shocks with a transitory effect on the inflation rate.

Lanari also claimed that there is no historical precedent for such a rapid disinflation process. However, Latin American history does not (at least for the moment) support this assertion. It’s not yet clear that the current disinflation has been more aggressive than in other instances, and this doesn’t even account for the ongoing recession. For example, the currency board of the 1990s achieved faster disinflation while expanding the economy. Economic growth is also observed when Ecuador dollarizes its economy. The next plot compares the evolution of the CPI in these two case and Milei’s disinflation. The CPI is set to 100 at the beginning of each stabilization plan:

Of course, Milei’s supporters might correctly argue that the initial inflation rates were not a result of Milei’s policies but rather a consequence of lingering Kirchnerista policies—inflation inertia from the previous government. This would, of course, apply to other stabilization plans as well.

Inflation did indeed decrease after Milei took office, and it did fall below pre-election levels. However, the 17,000% figure is an unnecessary statistical trick that undermines the administration’s credibility. And by implications, the credibility of libertarian thought.

Creo haberlo escuchado a Milei explicando que el 17.000% es el resultado de anualizar la inflación de la primera semana de diciembre del 2023, sería una inflación del 10,4% semanal anualizada da 17.000%.

In the following video Milei explains where the data comes from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rm9X0QcEszg min 15:45 ish. So basically companding the wholesale inflation from December which was around 54%. I would tend to agree with you that this might be a bit of cherry picking, however, given the existing dynamics at that time, I would not find surprising that inflation reached those levels. 17.000% or 6.000% does it really matter?