The Trade War Playbook

On January 18, 2026, President Trump announced 10% tariffs on eight European countries—Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—with the stated goal of pressuring Denmark to sell Greenland to the United States. The tariffs would rise to 25% by June if no deal materialized. Two weeks earlier, he had imposed a 25% tariff on certain AI chips. Throughout 2025, his administration enacted tariffs on steel, aluminum, copper, automobiles, and numerous other products, temporarily raising the average U.S. tariff rate to 27%—the highest level in over a century—before negotiations brought it down to roughly 17% by year’s end.

We’ve been here before. Multiple times. And it never ends well. Even with the recent U-turn that Trump seems to be taking on his latest tariff threat.

The pattern is the same regardless of who is in office. A government imposes tariffs to solve a domestic problem—“protecting jobs”, punishing what they argue to be unfair trade practices, or, in this case, acquiring territory. Trading partners retaliate swiftly and predictably. The economic damage exceeds whatever benefits were intended. Unintended consequences multiply. And the tariffs, originally presented as temporary measures, become nearly impossible to remove decades later.

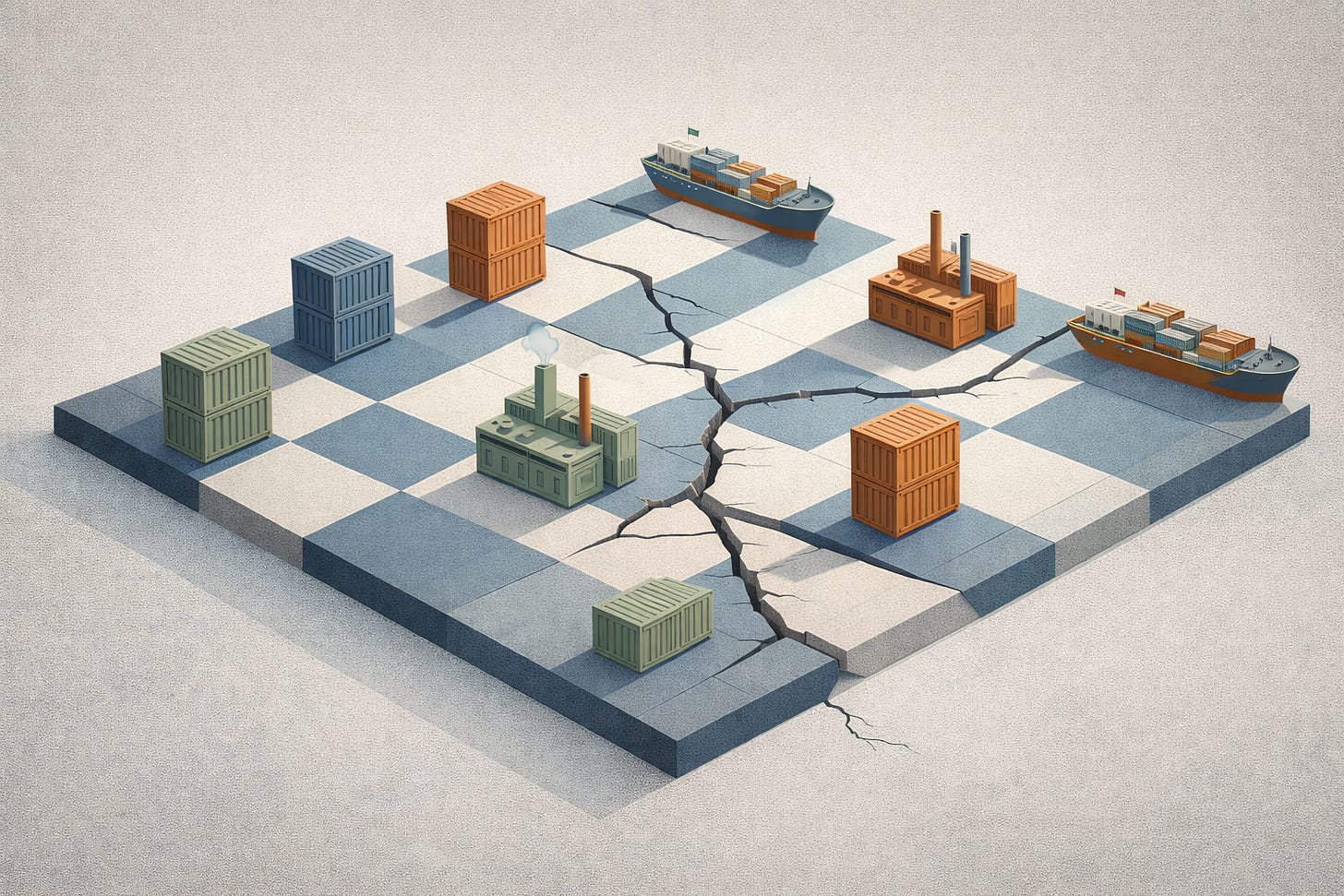

Trump’s tariffs are neither a smart chess move nor novel.

Smoot-Hawley: When Retaliation Becomes Contagion

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 remains the canonical case study of how trade wars spiral out of control. President Herbert Hoover signed it into law on June 17, 1930, despite a petition from 1,028 economists warning of the consequences. The Act raised already high import duties on a range of agricultural and industrial goods by some 20 percent.

The retaliation was quick and significant. By September 1929—before the bill even passed—Hoover’s administration had received protest notes from 23 trading partners. When threats failed to deter the U.S., countries acted. Canada, America’s most loyal trading partner, was among the first to respond in May 1930 by imposing new tariffs on 16 products accounting for approximately 30% of U.S. exports to Canada. Within two years of Smoot-Hawley’s passage, some two dozen countries had enacted retaliatory tariffs.

The numbers tell the story of a collapsing trading system. U.S. imports plummeted 66% from $4.4 billion in 1929 to $1.5 billion in 1933. Exports fell 61% from $5.4 billion to $2.1 billion over the same period. World trade decreased by approximately 66% between 1929 and 1934. Imports from Europe collapsed from $1.3 billion in 1929 to $390 million in 1932. U.S. exports to Europe declined from $2.3 billion to $784 million.

There was also political damage. Representative Willis Hawley, co-sponsor of the bill, lost his renomination. Senator Reed Smoot was one of 12 Republican senators who lost their seats in the 1932 elections. The Great Depression was already underway when Smoot-Hawley passed, but economists generally agree that the tariffs worsened the crisis by shrinking global trade, reducing employment in export-dependent industries, and contributing to bank failures abroad.

The key lesson from Smoot-Hawley isn’t just that retaliation happens—it’s that retaliation multiplies and becomes contagious. When major trading partners respond to tariffs with their own barriers, they create incentives for third countries to do the same. A bilateral dispute becomes a multilateral trade war. The damage cascades through the global economy in ways that dwarf the original “problem” the tariffs were meant to solve. A tariff is not a problem-solver tool. It is a problem magnifier tool.

We are observing a similar pattern under Trump’s presidency. China, Canada, Mexico, and the EU have all announced retaliatory tariffs in response to Trump’s measures. The EU is now discussing up to $108 billion in counter-tariffs following the Greenland announcement. Each retaliation creates pressure on other countries to protect their own interests, setting off the same contagion dynamic that characterized the 1930s.

The Chicken Tax: When “Temporary” Becomes Permanent

If Smoot-Hawley teaches us about retaliatory spirals, the Chicken Tax demonstrates a different pathology: how tariffs designed as temporary bargaining chips become permanent fixtures that distort markets for generations.

The story begins with chickens. Following World War II, intensive chicken farming in the U.S. drove prices down dramatically. American poultry producers began exporting to Europe, where chicken farming remained less efficient. By the early 1960s, U.S. chicken had captured nearly half the European market. France and West Germany, under pressure from domestic farmers, responded by implementing tariffs on U.S. poultry imports. By 1962, U.S. chicken exports to Europe had fallen approximately 67%, costing American producers roughly $26 million in lost sales.

President Lyndon Johnson retaliated in December 1963 with Proclamation 3564, imposing 25% tariffs on four European product categories: potato starch, dextrin, brandy, and light trucks. The tariffs on agricultural products and brandy were intended to match the economic harm to U.S. chicken producers. But the light truck tariff served a different purpose—it was a concession to United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther and Detroit’s Big Three automakers, who were concerned about growing imports of Volkswagen Type 2 pickups and vans.

The tariffs on potato starch, dextrin, and brandy were eventually lifted through subsequent trade negotiations. The 25% tariff on light trucks? Still in effect today, more than 61 years later. The chicken dispute that prompted the tariff was resolved decades ago. The tariff remains.

The Chicken Tax’s endurance illustrates three basic public choice principles.

First, tariffs create winners who lobby intensely to maintain protection. The Big Three automakers—Ford, GM, and Chrysler—have enjoyed 60 years of reduced competition in the light truck and pickup segment, their most profitable vehicles. These concentrated benefits create powerful political support for keeping the tariff. Automotive unions join this coalition, arguing that removing the tariff would cost American jobs. Both political parties support the tariff, making its removal virtually impossible despite bipartisan acknowledgment that it has outlived any legitimate purpose.

Second, the tariff has fundamentally reshaped the U.S. auto market in ways that would be painful to unwind. By effectively excluding foreign competition from the light truck segment, the Chicken Tax allowed domestic manufacturers to focus on ever-larger, more profitable trucks and SUVs. This strategic choice left them vulnerable when gasoline prices spiked, and consumer demand shifted toward more fuel-efficient vehicles. The market distortions created by six decades of protection cannot be unwound overnight without significant disruption.

Third, over time, the tariff’s original justification is forgotten while the protection it provides becomes institutionalized. How many Americans today know that the 25% tariff on imported trucks exists to retaliate against 1960s European chicken tariffs? The disconnect between the tariff’s original purpose and its continued existence doesn’t matter politically. What matters is that powerful constituencies benefit from it, and removing it would generate visible costs (plant closures, job losses) while the benefits (lower prices, more choices, industry innovation) remain diffuse and harder to see.

The distortions are substantial. Foreign automakers have gone to extraordinary lengths to circumvent the tariff. Subaru added welded-in rear-facing jump seats to its BRAT pickup to reclassify it as a passenger vehicle subject to only 2.5% duty. Ford shipped Transit Connect vans from Turkey with rear seats, windows, and seat belts, then stripped them at a Baltimore facility to convert them back to cargo vans—a process that cost hundreds of dollars per vehicle but saved thousands in tariffs. In 2024, Ford settled with the Justice Department, paying $365 million in tariffs and penalties for these practices. Mercedes-Benz ships Sprinter vans from Germany in passenger configuration, then converts them at a South Carolina facility, adding about 9% to the cost but still saving 16% compared to the tariff.

The real cost falls on American consumers and businesses. The tariff keeps prices artificially high for trucks and vans while limiting choices. A Toyota IMV 0 pickup, sold in other markets for around $10,000, cannot be profitably imported to the U.S., where the Chicken Tax would add thousands to its price. American buyers face a market where the least expensive new pickup truck costs over $25,000—more than double what a basic utility truck would cost absent the tariff protection.

The pattern is consistent. Nixon’s 1971 import surcharge, Reagan’s 1980s tariffs on Japanese goods, Bush’s 2002 steel tariffs, Trump’s first-term trade war—each followed the same script: temporary measures, retaliation, economic costs exceeding benefits, short-term political incentives trumping economic sense.

What to Expect

The 2025-2026 tariff escalation is following the historical playbook with remarkable fidelity. Tariffs announced on national security grounds. Retaliation swift and targeted at politically sensitive products. Negotiations conducted through threat and counter-threat. Trade agreements that existed for decades are thrown into question. Allies treated as adversaries.

The Greenland tariffs offer a clear example of the pattern. Eight U.S. allies—all NATO members—are being hit with tariffs not for any trade violation or unfair practice, but because they back Greenland and won’t pressure Denmark to sell territory it has no intention of selling. The economic justification is non-existent. The tariffs exist purely as coercive leverage for geopolitical aims. When those aims prove unrealizable, what happens to the tariffs? If history is any guide, they’ll find new justifications and new constituencies, and they’ll remain in place long after everyone has forgotten about Greenland.

The retaliation is already mounting. The EU is discussing $108 billion in counter-tariffs. Canada is strengthening trade ties with China. Countries are accelerating negotiations on trade agreements that exclude the United States. The damage cascades as expected.

From a fiscal perspective, the tariff revenue isn’t free money. While the administration points to increased customs revenue, this represents a tax on American consumers and businesses, collected indirectly through higher prices. The Tax Policy Center estimates tariffs announced through December 4, 2025, will cost the average household about $2,100 in 2026. And on top of this estimate, we need to add the Greenland tariff hike. This is a regressive tax—lower-income households pay a larger share of their income. The notion that tariffs will generate enough revenue to fund government services or provide a “tariff dividend” doesn’t survive serious analysis.

History doesn’t offer policy recommendations, but it does provide evidence. When governments impose broad tariffs, trigger retaliation, let temporary measures become permanent, and believe this time is different—the pattern is consistent and the outcomes predictable. This time is not, and will not be, different.

This post was written with the assistance of Claude (Anthropic).

Fantastic breakdown of tariff pathologies. The Chicken Tax example is especially powerful becuase it shows how temporary measures become institutionalized once beneficiaries organize politically. Back in grad school studied how concentrated benefits and diffuse costs make these protections almost irrevocable regardless of original justification. The $365 million Ford settlement is a wild datapoint on compliance arbitrage incentives.