Dollarization is More than a Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

This original version of this post is co-authored with Emilio Ocampo.

In 1976, the renowned economist Robert Lucas (1937-2023) introduced a thought-provoking paper that reshaped economic analysis. Lucas argued against relying solely on historical data to predict the outcomes of changes in economic policy, particularly when dealing with aggregate variables like consumption and investment. According to Lucas, the parameters of econometric models are not constant in the face of policy shifts; they hinge on economic agents' expectations of those changes.

This essay has been devoted to an exposition and elaboration of a single syllogism: given that the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents, and that optimal decision rules vary systematically with changes in the structure of series relevant to the decision maker, it follows that any change in policy will systematically alter the structure of econometric models.

In the context of regime changes or institutional shocks, economic agents' expectations and, consequently, the parameters of explanatory models undergo modification. Simply put, predicting the consequences of a regime change necessitates factoring in altered expectations. In essence, behavior cannot be assumed to remain constant post-regime change. To accurately predict the effects of such change, Lucas asserted the need to model the fundamental parameters governing individual behavior—linked to preferences, technology, and resources (the "micro-foundations"). Once these parameters explain observed empirical regularities, they enable predictions of economic agent behavior under new regimes through aggregated individual decisions.

A vivid analogy by Tim Harford in The Undercover Economist Strikes Back (2014) simplifies the "Lucas Critique": If Fort Knox reduces security spending, a conventional macro analysis might advise further reductions due to the historical lack of thefts. However, the critique argues that this policy prescription disregards potential behavioral shifts on the part of thieves when they observe a reduction in security spending. Similarly, in economics, policy alterations can't be evaluated solely on historical patterns; the impact of those changes on agents' behavior must be integrated.

It is difficult to imagine a more abrupt, lasting, and profound institutional change in a monetary regime than a dollarization.

Thus, understanding the concept of dollarization extends beyond a mere extreme form of fixed exchange rate systems. It entails a profound institutional shift, not just a monetary transformation. Institutions comprise the formal and informal rules that mold economic agents' incentives. Any macro model aiming to anticipate the effects of external shocks should avoid assuming that changing the exchange rate regime is the sole transformation. Ignoring the "Lucas Critique," which emphasizes accounting for behavior shifts, oversimplifies the complex nature of dollarization.

Dollarization marks a significant shift in economic policy formulation. This transition is not merely an escalated fixed exchange rate regime; it encompasses a broader institutional change.

Well designed and implemented, dollarization does not only reduce the degrees of freedom of monetary policy but also those of fiscal policy.1 Policymakers must adapt their behavior. Additionally, the public also reacts to this change. It is incorrect, therefore, to analyze the impact of dollarization, assuming the economic agents’ behavior does not change.

Averting the error of projecting macro models solely by fixing the exchange rate demands considering other crucial parameters. Two illustrative examples drive this point:

There is no point in dollarizing because provinces will issue quasi-currencies: Comparing peso-denominated quasi-currencies with dollar-denominated ones highlights the disparity. Additionally, the impact of issuing quasi-currencies below market rates can trigger unforeseen consequences, undermining provincial finances and creating political turmoil. Issuing under-the-par quasi-currency would reduce government spending in real terms. To use the case of quasi-currencies during the 2001 crisis as a case against dollarization ignores the institutional component of dollarization and the Lucas Critique.

There is no point in dollarizing because it won’t solve fiscal deficits: Evidence from Ecuador showcases that dollarization can prompt more sustainable fiscal deficits due to altered political incentives. Fiscal discipline becomes more crucial under dollarization. Additionally, Argentinian historical evidence also shows that its budget is more balanced under a strict monetary regime, such as a currency board or a fixed exchange rate.

Ecuador dollarized with a fiscal deficit of 4.4% of GDP. However, within six years after dollarization, Ecuador achieved a fiscal surplus of 1% of GDP. Even though Rafael Correa increased government spending and deficits, his successors had to reduce both spending and deficits at a faster pace than Argentina.2

Dollarization dismantles the exchange rate's role as the primary policy adjustment mechanism. Instead, other reforms like labor reforms and trade liberalization step into this role. By shifting incentives for politicians and businesspeople, dollarization fosters a different behavior, distinct from when fiscal deficits could be monetized or monetary policies politicized. Dollarization gives the political space and incentive (in the margin) to move forward with other needed structural reforms.

Some Lessons from Ecuador’s Case

Ecuador provides insightful lessons that underscore the flaw in predicting Argentina's response to dollarization without considering the Lucas Critique.

The first one is that the announcement of dollarization triggered an inflow of deposits almost immediately. It is doubtful that announcing a fixed exchange rate regime would have produced such a behavior change in economic agents. The confidence shock that dollarization can produce is more impactful than that of a fixed exchange rate regime. What is interesting about this case is that bank deposits increased despite facing a negative real interest rate.

It is worth remembering that Ecuador was in default and going through deep banking and political crises. Contrary to some economists' concerns, a well-designed and adequately implemented dollarization must not result in a bank run.

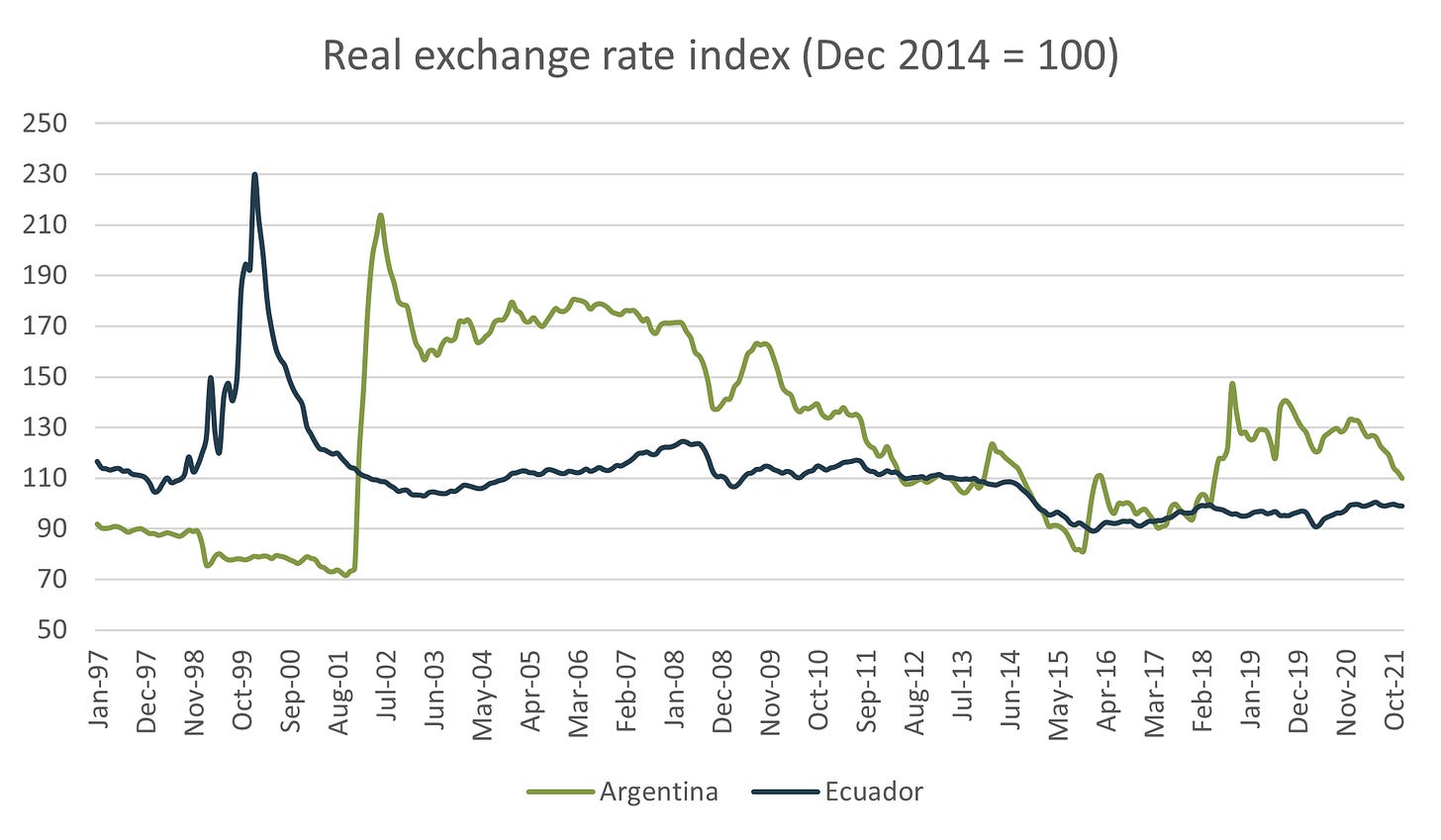

A second example is the impact of foreign shocks on the economic activity of a dollarized economy. Theory indicates that an economy with a fixed exchange rate regime is more vulnerable to foreign shocks due to an appreciation of the real exchange rate.

In theory:

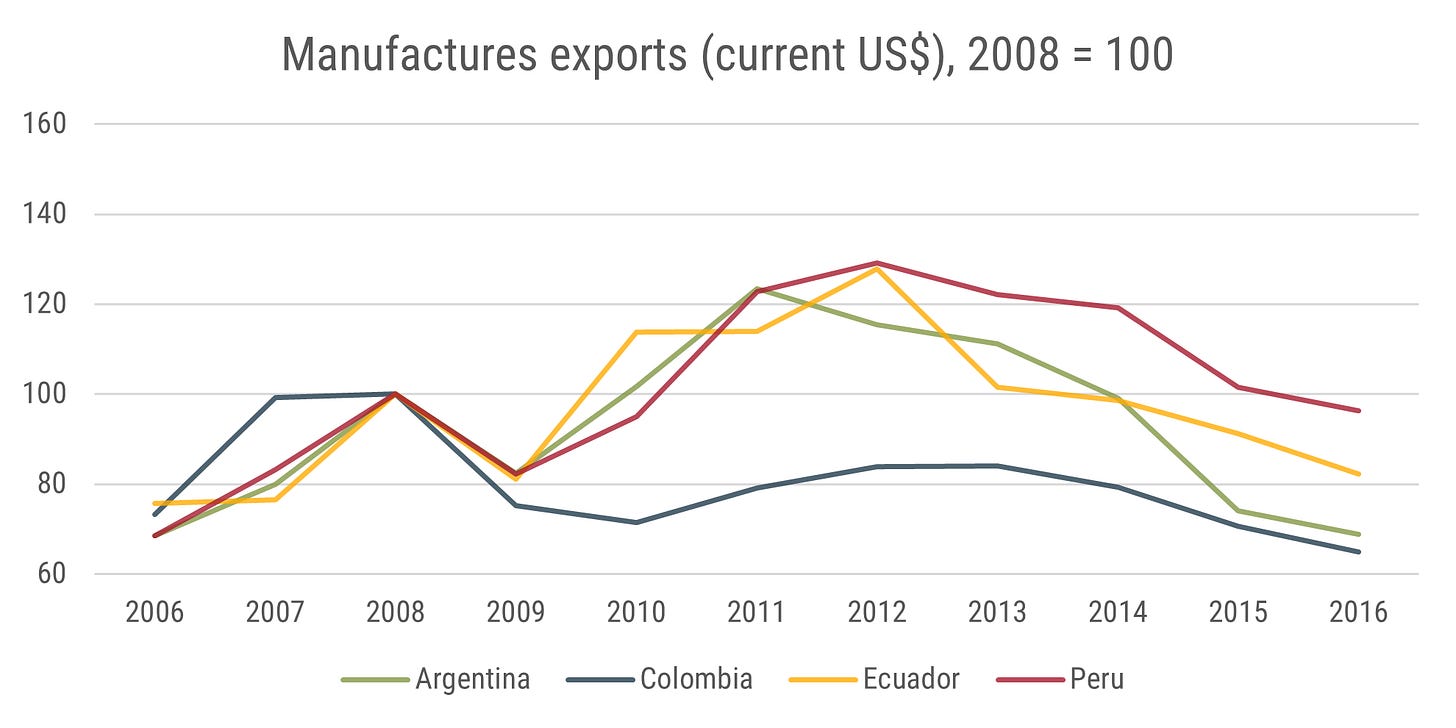

There are, however, some important differences among these economies. Ecuador is likely to suffer relatively more under the current juncture. Apart from facing an appreciating real exchange rate that will put it at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis neighboring countries, thereby limiting its ability to take advantage of rising external demand from the U.S. and Europe, it may be relatively more affected by the Chinese deceleration.

~ de la Torre, A., Levy-Yeyati, E., and Pienknagura, S. (2013, p. 30).

Reality:

As mentioned in a previous post, is possible for dollarized economies to handle foreign shocks better than Argentina can with its discretionary central bank. A similar result is observed during Covid-19.

A third example is Ecuador and Argentina's real exchange rate (RER) volatility. Given that the nominal exchange rate cannot compensate for the impact of foreign shocks, you should expect RER to be more volatile in a dollarized economy. But this is not what data shows when comparing Argentina and Ecuador. The dollarized economy has a more stable RER. Once again, the error consists in assuming that dollarization is just an exchange rate regime.

Studying international instances of dollarization is vital, not to argue dollarization is a panacea, but to understand its potential positive effects on economies like Argentina's. Recognizing the complexity of its advantages and drawbacks is crucial. Importantly, these real-world experiences often defy theoretical predictions; in such cases, it's the theory that falls short, not reality.

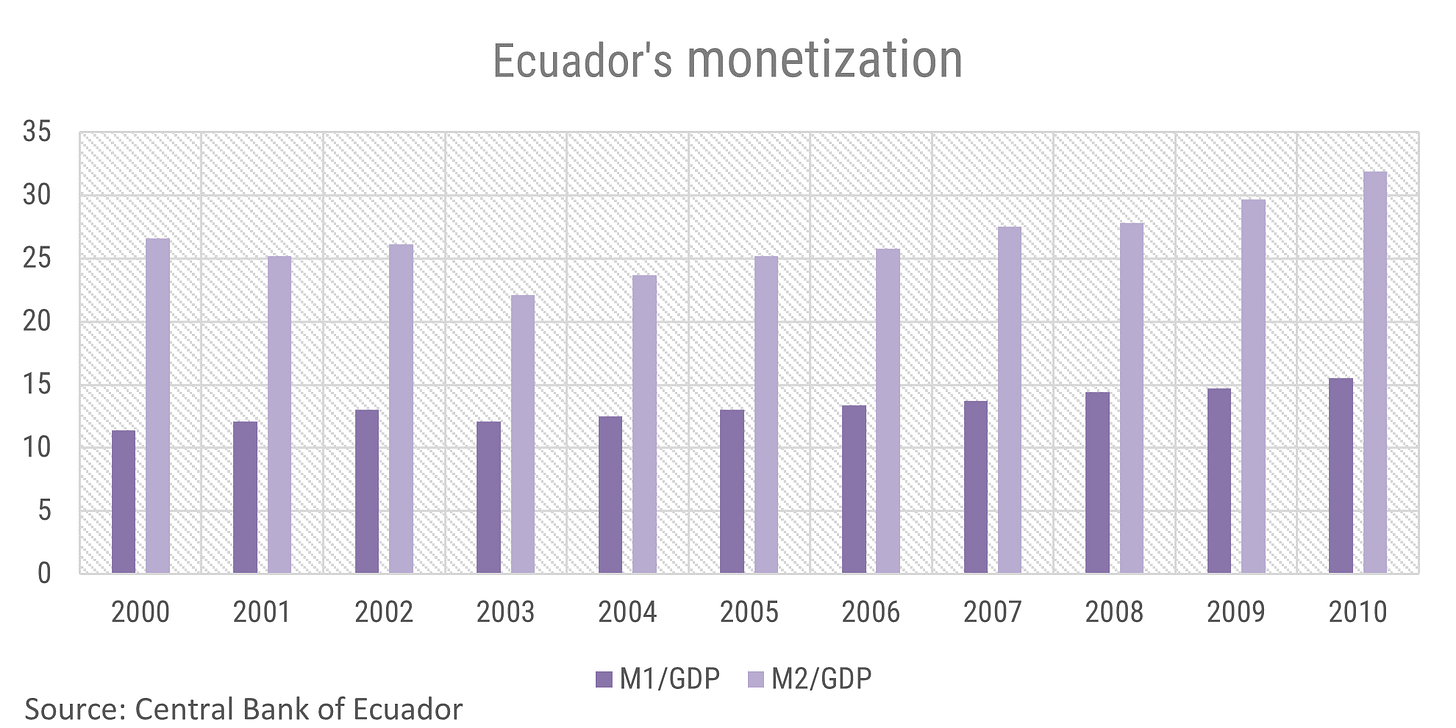

Monetary authorities’ degrees of freedom under dollarization depend on how this regime is implemented. On occasions, the monetary authority of a dollarized economy can change the money multiplier by regulating the required reserve level.

Correa’s spending and deficit can be explained, to a certain extent, by his degradation of the financial integrity of Ecuador’s dollarization. Correa forced banks to return their reserves and deposit them in the central bank. Following this, Correa used the central bank reserves to finance his deficits.

The original Spanish post can be found here.

Next: Dollarization and the real exchange rate.