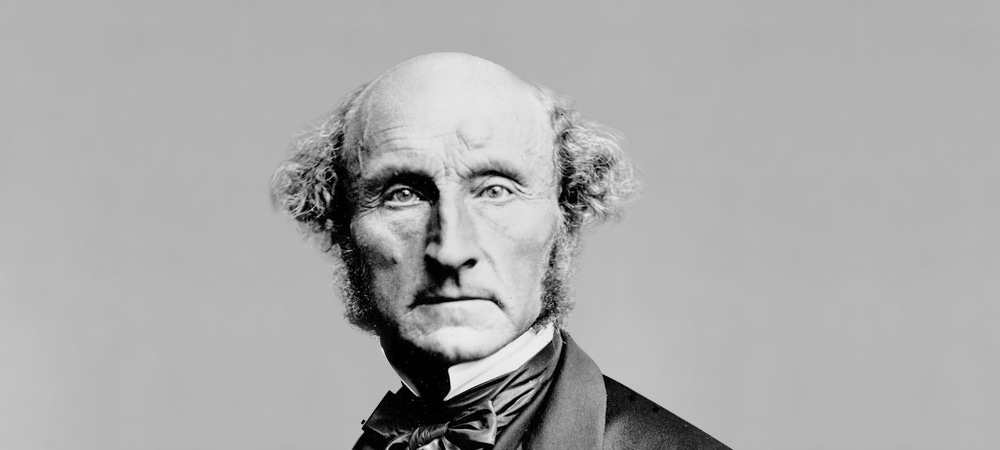

The classics versus the labor theory of value - Part III - John Stuart Mill

A cost-price theory is not the same than a labor theory of value

Mill’s price theory: Ricardo 2.0

John Stuart Mill’s popular Principles of Political Economy (PPE) is probably the work that best organizes and systemizes the view of Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

True to the classic tradition, Mill opens his discussion of value by distinguishing between the two meanings of the word value (PPE, pp. 436-437, bold added)1:

We must begin by settling our phraseology. Adam Smith, in a passage often quoted, has touched upon the most obvious ambiguity of the word value; which, in one of its senses, signifies usefulness, in another, power of purchasing; in his own language, value in use and value in exchange. But (as Mr. De Quincey has remarked) in illustrating this double meaning Adam Smith has himself fallen into another ambiguity. Things (he says) which have the greatest value in use have often little or no value in exchange; which is true, since that which can be obtained without labour or sacrifice will command no price, however useful or needful it may be. But he proceeds to add, that things which have the greatest value in exchange, as a diamond for example, may have little or no value in use.

Without developing a marginal theory of value, Mill closes this paragraph by connecting value of use (utility) with value of exchange (price); the former sets the upper limit of the latter (PPE, p. 437):

The use of a thing, in political economy, means its capacity to satisfy a desire, or serve a purpose. Diamonds have this capacity in a high degree, and unless they had it, would not bear any price. Value in use, or as Mr. De Quincey calls it, teleologic value, is the extreme limit of value in exchange. The exchange value of a thing may fall short, to any amount, of its value in use; but that it can ever exceed the value in use implies a contradiction; it supposes that persons will give, to possess a thing, more than the utmost value which they themselves put upon it as a means of gratifying their inclinations.

As a warning against any confusion, Mill immediately continues with the following caution(PPE, p. 437, bolds added):

The word Value, when used without adjunct, always means, in political economy, value in exchange […]

Like his predecessors, Mill also argues that a thing without utility will have no price (PPE, p. 442, bolds added):

That a thing may have any value in exchange [price] , two conditions are necessary. It must be of some use; that is (as already explained), it must conduce to some purpose, satisfy some desire [utility]. No one will pay a price, or part with anything which serves some of his purposes, to obtain a thing which serves none of them. But, secondly, the thing must not only have some utility, there must also be some difficulty in its attainment [scarcity].

Soon after, Mill continues (PPE, p. 437, bolds added):

The difficulty of attainment which determines value is not always the same kind of difficulty. It sometimes consists in an absolute limitation of the supply. There are things of which it is physically impossible to increase the quantity beyond certain narrow limits. Such are those wines which can be grown only in peculiar circumstances of soil, climate, and exposure. Such also are ancient sculptures; pictures by old masters; rare books or coins, or other articles of antiquarian curiosity. […]

But there is another category (embracing the majority of all things that are bought and sold), in which the obstacle to attainment consists only in the labour and expense requisite to produce the commodity.

Mill reaches the same conclusion as Ricardo. In the long run, the natural (equilibrium) price is determined by the costs of labor and capital (land is not included). In contrast, shortages and surpluses explain price movements in the short run. In Mill’s own words (PPE, p. 456, bolds added):

To recapitulate: demand and supply govern the value [price] of all things which cannot be indefinitely increased; except that even for them, when produced by industry, there is a minimum value [price], determined by the cost of production. But in all things which admit of indefinite multiplication, demand and supply only determine the perturbations of value [price], during a period which cannot exceed the length of time necessary for altering the supply. While thus ruling the oscillations of value [price], they themselves obey a superior force, which makes value [price] gravitate towards Cost of Production, and which would settle it and keep it there, if fresh disturbing influences were not continually arising to make it again deviate. To pursue the same strain of metaphor, demand and supply always rush to an equilibrium, but the condition of stable equilibrium is when things exchange for each other according to their cost of production, or, in the expression we have used, when things are at their Natural Value.

What are the costs of production for Mill? Labor and capital (PPE, p. 473):

Thus far of labour, or wages, as an element in cost of production. But in our analysis, in the First Book, of the requisites of production, we found that there is another necessary element in it besides labour. There is also capital; and this being the result of abstinence, the produce, or its value, must be sufficient to remunerate, not only all the labour required, but the abstinence of all the persons by whom the remuneration of the different classes of labourers was advanced. The return for abstinence is Profit. […] Profits, therefore, as well as wages, enter into the cost of production which determines the value of the produce.

Mill explains landowners’ income like Ricardo does. Landowners receive a rent based on the productive differential next to the marginal land (PPE, p. 473, bolds added):

Rent, in short, merely equalizes the profits of different farming capitals, by enabling the landlord to appropriate all extra gains occasioned by superiority of natural advantages. If all landlords were unanimously to forego their rent, they would but transfer it to the farmers, without benefiting the consumer; for the existing price of corn would still be an indispensable condition of the production of part of the existing supply, and if a part obtained that price the whole would obtain it. Rent, therefore, unless artificially increased by restrictive laws, is no burthen on the consumer: it does not raise the price of corn, and is no otherwise a detriment to the public, than inasmuch as if the state had retained it, or imposed an equivalent in the shape of a land-tax, it would then have been a fund applicable to general instead of private advantage.

Mill’s price theory is similar to that of Ricardo:

(cost of labor + cost of capital) → equilibrium price

Mill neither is free of the circular reasoning of the classic’s price theory (PPE, p. 347, bolds added):

[Ricardo] assumes, that there is everywhere a minimum rate of wages: either the lowest with which it is physically possible to keep up the population, or the lowest with which the people will choose to do so. To this minimum he assumes that the general rate of wages always tends; that they can never be lower, beyond the length of time required for a diminished rate of increase to make itself felt, and can never long continue higher. This assumption contains sufficient truth to render it admissible for the purposes of abstract science; and the conclusion which Mr. Ricardo draws from it, namely, that wages in the long run rise and fall with the permanent price of food, is, like almost all his conclusions, true hypothetically, that is, granting the suppositions from which he sets out.

In some sense, Mill’s work represents the culmination of the classic theoretical construction. Mill’s work raises the classic theory's prestige to its highest levels, a barrier to entry to the new marginal theory. It is with historical irony that he will claim that the theory of price is complete and there is nothing else to add, that all that remains is applying the idea to what at first sight looks perplexing (PPE, p. 436, bold added):

Happily, there is nothing in the laws of value [price] which remains for the present or any future writer to clear up; the theory of the subject is complete: the only difficulty to be overcome is that of so stating it as to solve by anticipation the chief perplexities which occur in applying it: and to do this, some minuteness of exposition, and considerable demands on the patience of the reader, are unavoidable.

The phrase was initially written in 1848 and remained in future editions, including 1871, the same year the marginal revolution shattered the classic’s price theory. Mill also seems unaware of the circular reasoning his price theory suffered from.

Conclusions

There is a common argument in the Smith-Ricardo-Mill price theory. The determinant of an item's equilibrium (long run) price is its production cost. Besides the inclusion or not of the cost of land, the approach to price is similar across these thinkers.

Like Smith and Ricardo, reading Mill’s treatment shows that he is talking about a cost → price theory and not a labor → utility theory.

In the next entry, I’ll discuss Marx, who shares this “classic” approach to price theory.

Next: Karl Marx

Mill’s comment on Smith’s ambiguity suggests he may not have had access to his Lectures of Jurisprudence, where he solves the paradox of value with a demand and supply analysis.